Al Hirschfeld, the Algonquin, & Why I Moved to New York City

Hunting for NINAs at the home of the roundtable.

September 10, 2025

Midtown, New York

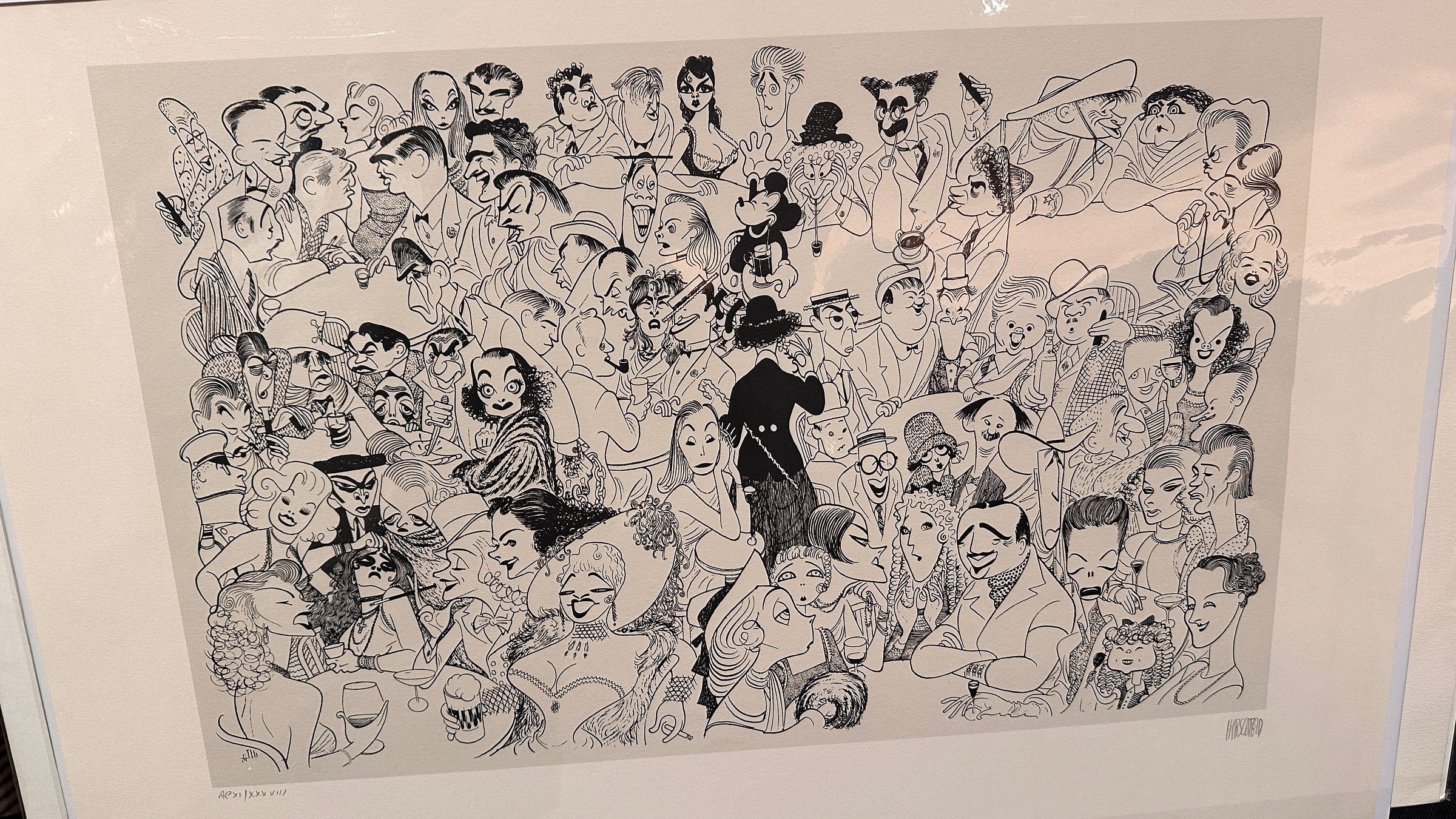

Tonight, I was invited to the Al Hirschfeld reception at the Algonquin Hotel, home of the famous Algonquin Round Table. We were celebrating both the new poster book about Hirschfeld’s work on Sondheim shows and the collection of his iconic work. This is the first NYC gallery showing of Al Hirschfeld’s work in over a decade.

I grew up poring over Hirschfeld’s work, tracing his lines with my eyes, learning how much you can do by leaving most of it out. To stand in the Algonquin, where he once drew his peers, and be surrounded by his work alongside people I know—it reminds me this is exactly why I moved here. To be around it, learn from it, absorb it, and (hopefully) get better.

Declared a Living Landmark in 1996 and a Living Legend by the Library of Congress in 2000, Al Hirschfeld’s work has appeared in every major publication of the last 9 decades, including his 75 years in the New York Times. He was undeniably the greatest caricaturist New York has ever produced (even if he didn’t consider himself one… He called himself a characterist, which isn’t a word.)

But I digress. Here was a man who could make an entire performance materialise with a single swoopy line, scratched out laboriously from the sublime comfort of an old Koken barber’s chair.

As the throng of collectors and donors shmoozed and kibitzed, David Leopold, the Hirschfeld Foundation’s creative director, spoke with his usual mix of scholarship and showmanship. He’s the keeper of the archive, the guy who knows where all the NINAs are hidden.

I, meanwhile, was quietly bleeding in the corner. Somewhere while walking the three avenues from my apartment, I’d manage to jab myself with a golf pencil I’d stuffed in my pocket. I walked the Oak Room sucking my bleeding thumb like a child, trying to look like someone who belonged at an art opening while also staunching the world’s most persistent paper-cut. In my Larry David version of events, the blood would have landed on a priceless original Hirschfeld. Luckily, it just smeared on my copy of the new book (cover below).

I ran into Charlie Kochman, editor-in-chief of Abrams ComicArts—the publisher behind Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and the very book that was being launched tonight. We caught up before he bumped into his childhood friend, John Leguizamo, who was holding court like only John Leguizamo can. It was one of those surreal New York nights where you realise you’ve accidentally wandered into someone else’s anecdote.

If you were immortalised by Hirschfeld, you were minted. It meant you’d made it. Every Sunday, readers of the New York Times would flip to the Arts & Leisure section for his drawing, then count the hidden NINAs—the name of his daughter, tucked into hair and sleeves. The number beside his signature told you how many to find. Parents passed the page to their kids like a puzzle. An entire generation grew up on that ritual.

In 1932, after returning from 10 months of living in the high contrast light of Bali (by way of selling art to Charlie Chaplin to afford a ticket home) Hirschfeld defined himself with clear, swooping line work. People assume it was a brush. It wasn’t. It was a fine dip pen and nib, scratching music into illustration board. His line is deceptively simple, impossibly alive.

There’s a documentary—The Line King— (above) that was nominated for an Oscar. If you want the short course in Hirschfeld, start there. Then go stand under the marquee of the Al Hirschfeld Theatre and try not to grin at the fact that a cartoonist’s name lights Broadway.

Hirschfeld himself was a night owl, out at Broadway or jazz, then back at the studio drawing into the wee small hours. He never reviewed the plays; he just drew them. Last year, I reviewed Moulin Rouge! at Al’s namesake theatre (which also happens to live on my block). I was not as diplomatic. That’s something Hirschfeld never did—he let the line do the talking.

Later in the night, I found myself in the corner talking with Peter de Sève—the New Yorker cover illustrator whose lines are just as envy-inducing. We drifted between cartoon gossip and shop talk about gag ideas and AI. It felt like Hirschfeld would’ve approved: a room full of ink-slingers comparing notes, half serious, half ridiculous, all of us trying to make a line do something it probably shouldn’t.

’til next time,

Your pal,

Exhibition: Strokes of Genius: Hirschfeld at the Algonquin

Where: The Algonquin Hotel, Oak Room, 59 W 44th St, NYC

When: Sept 9–20th, noon–7 pm daily

Presented by: The Al Hirschfeld Foundation

The exhibition features more than two dozen works from stage, screen, and concert hall. Everything is for sale, with proceeds supporting the Foundation: There’s Gershwin, a Carol Burnett TV Guide cover painting, and portraits of Algonquin Round Table members Alexander Woollcott and Robert Benchley. The centrepiece is a Sondheim spread worthy of its own overture: the original drawing for Do I Hear a Waltz?, lithographs for Forum (Nathan Lane), Passion, Putting It Together, and a 1977 Sondheim portrait signed by Hirschfeld. There’s an etching of Gypsy with Ethel Merman, plus performer-signed giclées of Sunday in the Park with George (edition of 15), Julie Andrews in Putting It Together (edition of 15), and a Sondheim 1999 portrait signed by Sondheim himself—one of only four in existence.

The book:

This handsome volume presents 25 favorite Al Hirschfeld portraits drawn from Stephen Sondheim’s musicals. The art prints in this oversize poster book can be easily removed and framed, making it an ideal gift for Sondheim fans.

This first volume in a series of deluxe Hirschfeld poster books contains art drawn from life before the opening night of each of Sondheim’s productions. On the reverse side are rare, ancillary images from the archives, as well as an introduction by Bernadette Peters, an essay by Ben Brantley, and text by David Leopold, Hirschfeld’s archivist and creative director of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation.

Hirschfeld’s images capture the essence of the performances even better than the photographs of the shows. All of Sondheim’s best-known plays are included—West Side Story, Follies, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Sweeney Todd, Merrily We Roll Along, and Sunday in the Park with George.

I thoroughly enjoyed this post, Jason! Thanks for helping us feel like we were along with you at the event.

I didn't know about Hirschfeld putting a number by his signature to indicate how many times Nina is hidden in a caricature. Very cool!

Sounds like the quintessential NYC experience! I’m a native New Yorker that grew up hunting NINAs, and I thank you for sharing your experience. It’s a game changer when the first post I read in the morning is joyful!