'How do you decide who you're going to be when you get up in the morning?'

How one piece of advice from Edward Sorel in 2022 changed my career and helped me finally find my own style.

The question landed like a perfectly timed comedic slap.

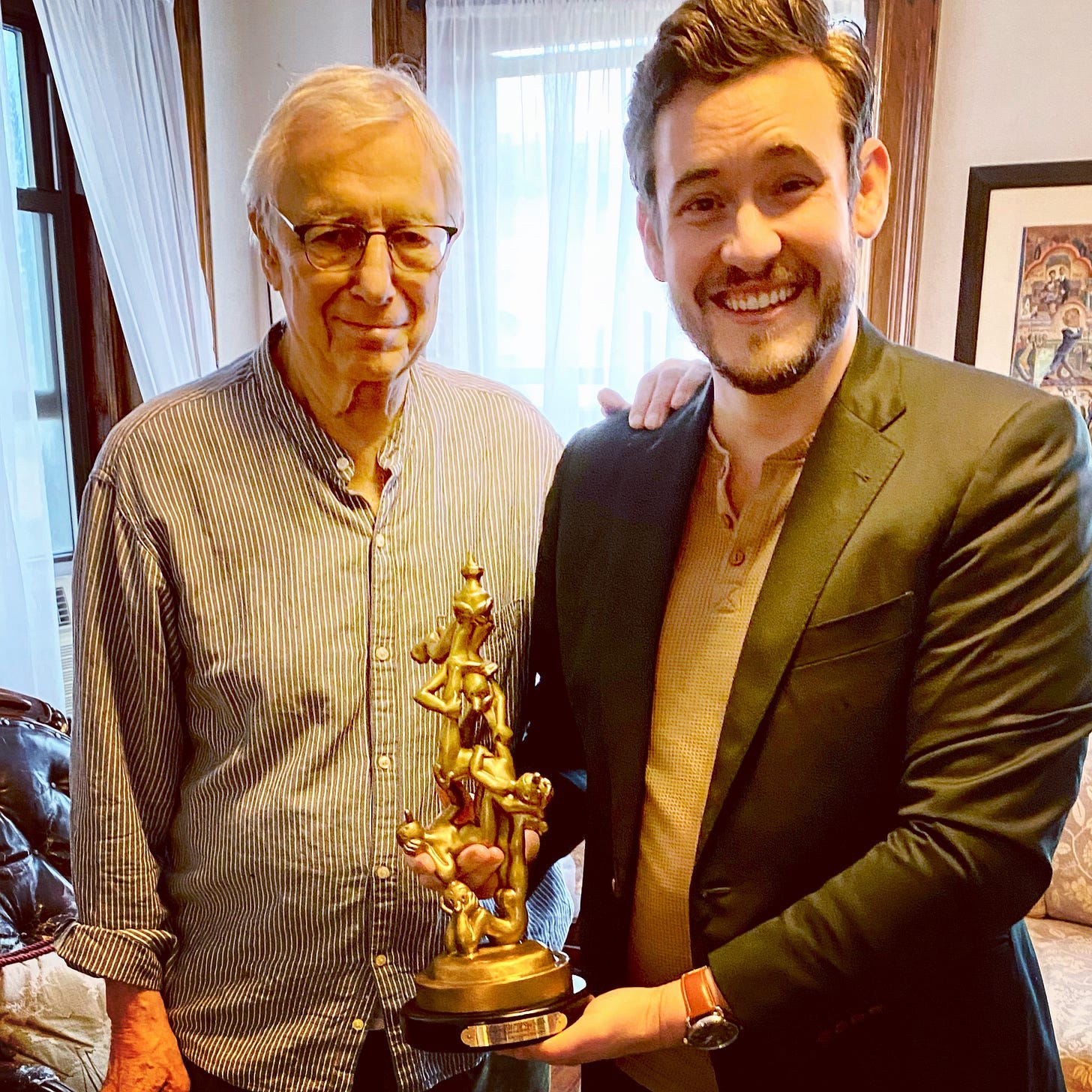

It was 2022, and I was sitting at my drawing board, having just returned from the profusely illustrated Manhattan apartment of Edward Sorel, 96-year-old satirical legend, keeper of every important illustration award, and the man whose caricatures have been making politicians sweat since the Eisenhower administration.

Sorel is, without question, one of the most iconic satirical illustrators in America. His recent memoir, Profusely Illustrated, is a testament to his prolificity. The book details a series of accidents that led him to become more of a caricaturist than a traditional illustrator. If you’ve ever been to the sunken dining room at the Monkey Bar on E54th (pictured above), you’ve been immersed in his unmissably unique, energetic line.

Needless to say, I’m a fan.

I was nervous to finally get an opportunity to meet him. My friend Karen Green, Curator for Comics and Cartoons at Columbia University, had teed up the meeting during which we got to hand Mr. Sorel his Reuben Award, the highest honour bestowed by his peers in the cartooning industry. He won towards the end of the pandemic years, and it wasn’t safe for him to travel.

He really was chuffed. He called it “the best kind of award you can get.” The acceptance speech was recorded from his apartment during the Omicron spike. He concluded it by saying,

“I’ve found making satirical drawings a most satisfying way to go through life. What was especially satisfying was seeing my drawings get better and better as the years went on.“

(Video recorded by Karen Green)

From the moment we stepped into his hand-illustrated elevator, a knot formed in my stomach. I felt like a complete dilettante calling myself a cartoonist in his company. I’d heard stories that he could be a bit of a misanthropic grump. Upon stepping through the door, the knot loosened as I quickly discovered he is, in fact, not a grump. (He’s just a New Yorker.)

Oh, and I wasn’t kidding: the elevator to his apartment might just be the greatest one in Manhattan. It was like riding up to heaven in a Wonka contraption designed by Ludwig Bemelmans after a three-martini lunch.

(Okay, I’ll cool it with the gushing— I thought you should know how much his professional opinion means to me.)

Over coffee and baked Jewish delicacies, Sorel shared with Karen and me that he was working away on a full-page illustration for Esquire and couldn’t quite land a likeness the way he wanted. It was 3:30 pm, and he’d been at it all day. He needed the break.

I was both relieved and horrified to learn that this feeling —with which I’m intimately familiar— is still something that still haunts illustrators no matter how long they’ve been at the drawing board. Having an established style doesn’t rescue you from this all-consuming affliction. Sorel, at the age of 95, is still as dedicated to his process as ever. (Yes, he’s still working at 95. Cartoonists don’t retire.)

He invited us down the narrow hallway to his studio. The walls were adorned with framed originals; personal gifts by everyone from David Levine to Peter Arno— a continuous Pantheon of New Yorker cartoonists and illustrators guiding the way to the one place Sorel spends his days: a small, sacred room with a huge black drawing board framed by giant wooden flat files and desks, drawers bursting with iconic art.

Strewn around the studio floor and tables were page upon page with the slightest variations of the same illustration— evidence of an explosive dedication to getting the piece down the way he wanted it. He admitted he was having an unsettling battle. He’d clearly gone a few rounds, but it hadn’t defeated him. There were scraps that he liked. He remained determined.

His commitment to never tracing, never light-boxing, and trying to capture the spontaneity of a pencil sketch in his finished inks is a chief reason his style is so sought-after. It’s also the reason it’s so challenging to turn out work with such energetic quality. It takes a lot of effort to make it look effortless.

Sidenote: I did snap a photo of his studio, but I won’t post it here because I didn’t get his permission to share it, and, frankly, if anyone published a private photo of what my studio looked like while I was mid-project, I’d take ‘em for a quiet drive to the Pine Barrens without hesitation. (I’m working on it with my therapist.)

Well. The afternoon visit concluded. We jumped in a cab to Zabar’s, where he asked about my work before we parted ways with a wave (handshakes were still very risky). I was reeling.

Soon after, Sorel generously took the time to go through a large selection of my art: illustrations, gag cartoons, caricatures, comic strips— the works. I was very anxious to share it with him, but I knew the discomfort would be worth his feedback. It was generous of him to offer.

Once he’d sat with my garbage fire of a portfolio, he gave me the most valuable, candid feedback I’ve ever received as a cartoonist. It sank into my subconscious and has lived there, rent-stabilised, ever since. I’m sharing it with you because I think it might be helpful for your own development:

He said,

“Jason, I'm overwhelmed by the drawings, not so much by the quantity, as by the number of different styles—everything from broad slapstick to sensitive portraits done with a delicate line.

How do you decide who you're going to be when you get up in the morning?”

That last line knocked me back in my chair. It wasn’t exactly advice, but it was something far more valuable; a crucial question I’d avoided asking myself for as long as I’ve been working. He was completely right: I didn’t have a discernible style of my own. You couldn’t pick my work out of a line-up if you were the best Art Director on Earth. This was not a compliment.

Every artist who has ever ‘influenced’ my work has had a distinctive style that you could pick a mile away. You can recognise Mort Drucker from the moon. (and Searle from Saturn.)

He was right, of course. I'd spent so many years being a professional shape-shifter; adapting to whatever brief landed on my desk, aping styles to match client comps, that I'd never developed my own voice. I'd been wearing so many artistic masks, I'd forgotten what my actual face looked like underneath.

One good thing about making your living as a cartoonist is that if you’re lucky, you get to do varied and interesting projects that challenge you and push you in directions you wouldn’t have gone without that day’s brief. If you’re unlucky, you get boring, unfulfilling projects that make you question your career choices. You take jobs you don’t want to pay the rent, and you begin resenting the work. (If you’re really unlucky, you don’t get any work at all.) On balance, most professional cartoonists get a mix of both good and bad jobs.

But, there’s one thing they should always carve out time for, which I neglected to do for most of my career:

Drawing for yourself.

I was so preoccupied with turning in jobs that paid my rent that I never actually prioritised what got me so obsessed with cartooning in the first place: Play. Drawing for — God forbid— fun!

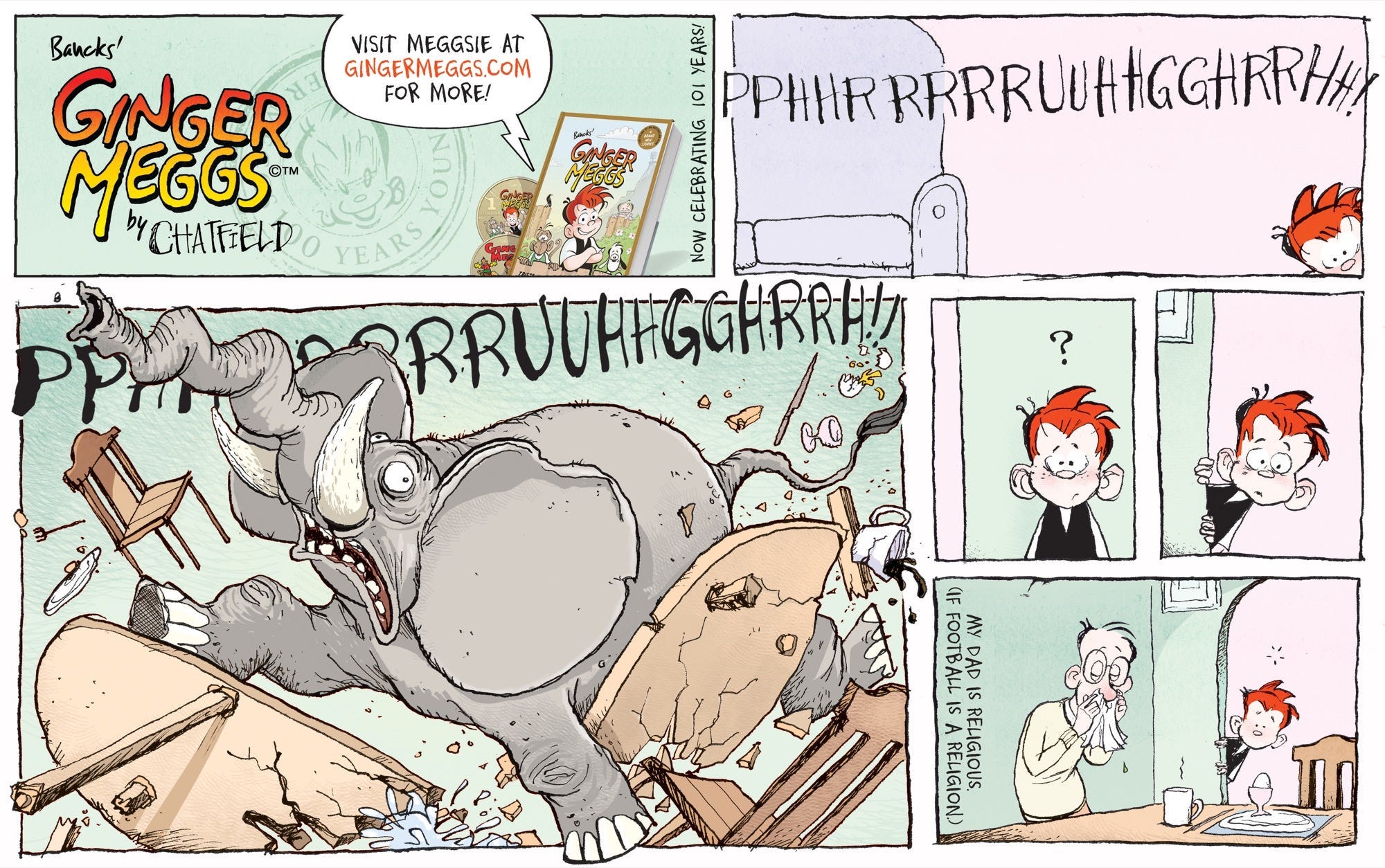

After Ed gave me that advice (I have no right calling him Ed, but it feels cheeky), I went back to my drawing board and started giving myself permission to play. I’d been doing a syndicated legacy comic strip every day for 16 years, and I’d been apeing someone else’s style that whole time; it was like wearing someone else’s clothes to work. I only got to draw in my own style in the final year the strip was running, and only ever in the Sunday strips.

I decided to start carving out time in my calendar on weekends for just drawing with no end goal in mind— drawing for the sake of drawing. Experimenting. Seeing what fell out of my pen. And I would do it in the tub. With a scotch. (I now refer to it as #ScotchbathSunday) Get on board.

There’s something about the safety and closure of the shape of a tub that encourages a deep focus. Plus, how great is scotch?

I chose the tools I enjoy using the most: physical, tangible, traditional art materials—nothing digital—the kind that keep me on my toes and learning as I go: namely, my Hunt #101 Imperial nib and some non-waterproof ink. (One time, I accidentally tipped some waterproof ink into the bath and came out looking like a coal miner. Meet me in the comments.)

The Glory and Betrayal of the Hunt #101 Imperial Nib.

I’d tried every nib in the book before I discovered this obscene little bastard— and I have the late, great Richard Thompson to thank. It was designed for ornamental calligraphy, specifically copperplate or Spencerian calligraphy. But sweet Jesus, it’s fun to draw with. Richard once described it thusly:

I’ve always been in the school of thought that “It isn’t the tool, it’s the person using it.” I’ve seen artists turn out masterpieces using whatever was within arm’s reach. However, I’ve also seen artists discover a tool that allows their voice to be clarified so perfectly, a glove that fits their hand to allow them just the right grip on their style. For me, it was this nib that distilled my authentic style. I’ve been using it as often as I can.

It did require the ability to play loosely with every variation I could muster— and I made a promise to myself (do this, tell me if it works for you) that everything I drew in my sketchbook would never be seen by another pair of human eyes. That’s what sketchbooks are for, by the way, not for posting on Instagram. But that’s another post for another time. (It has also already been articulated perfectly by Kyle T Webster.)

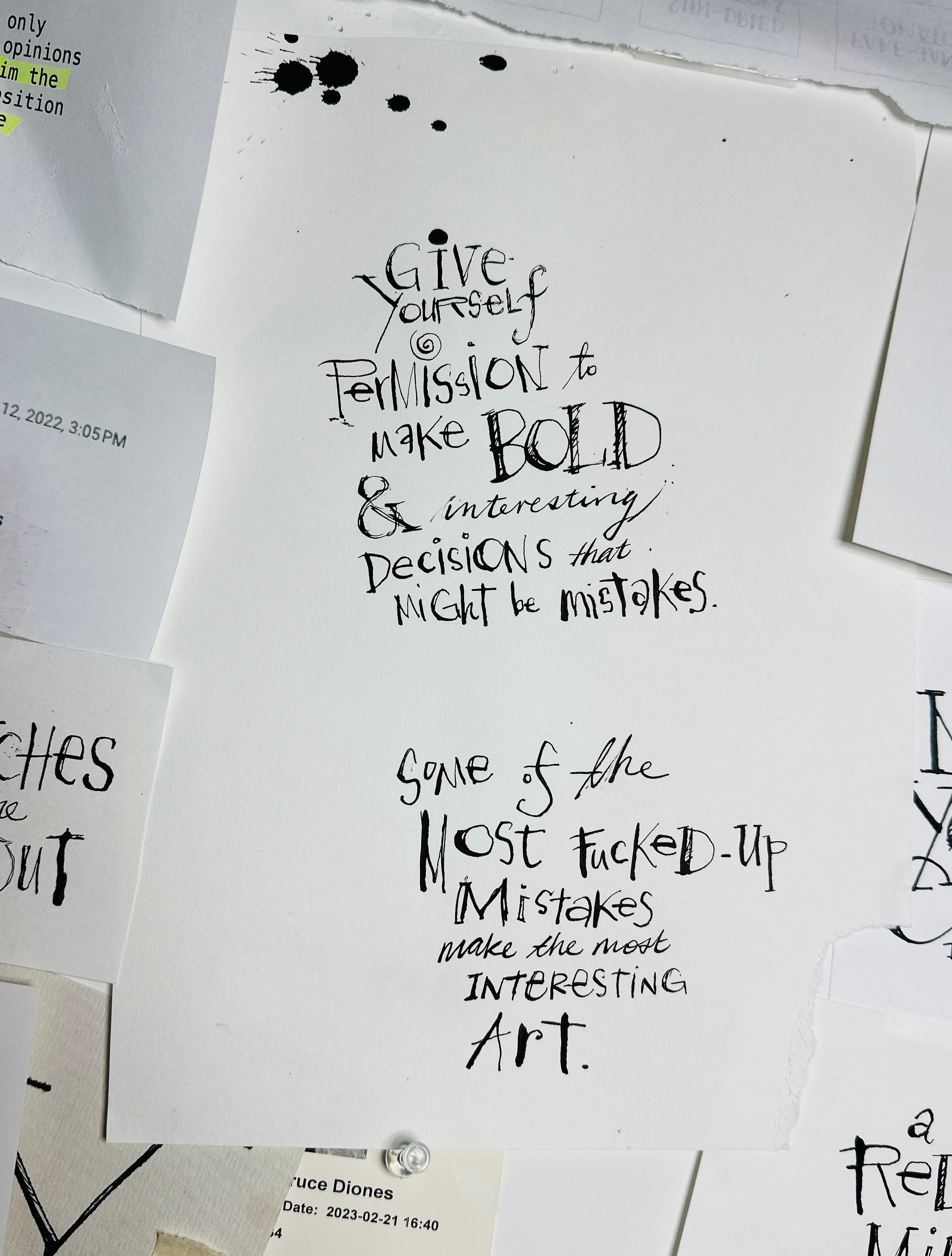

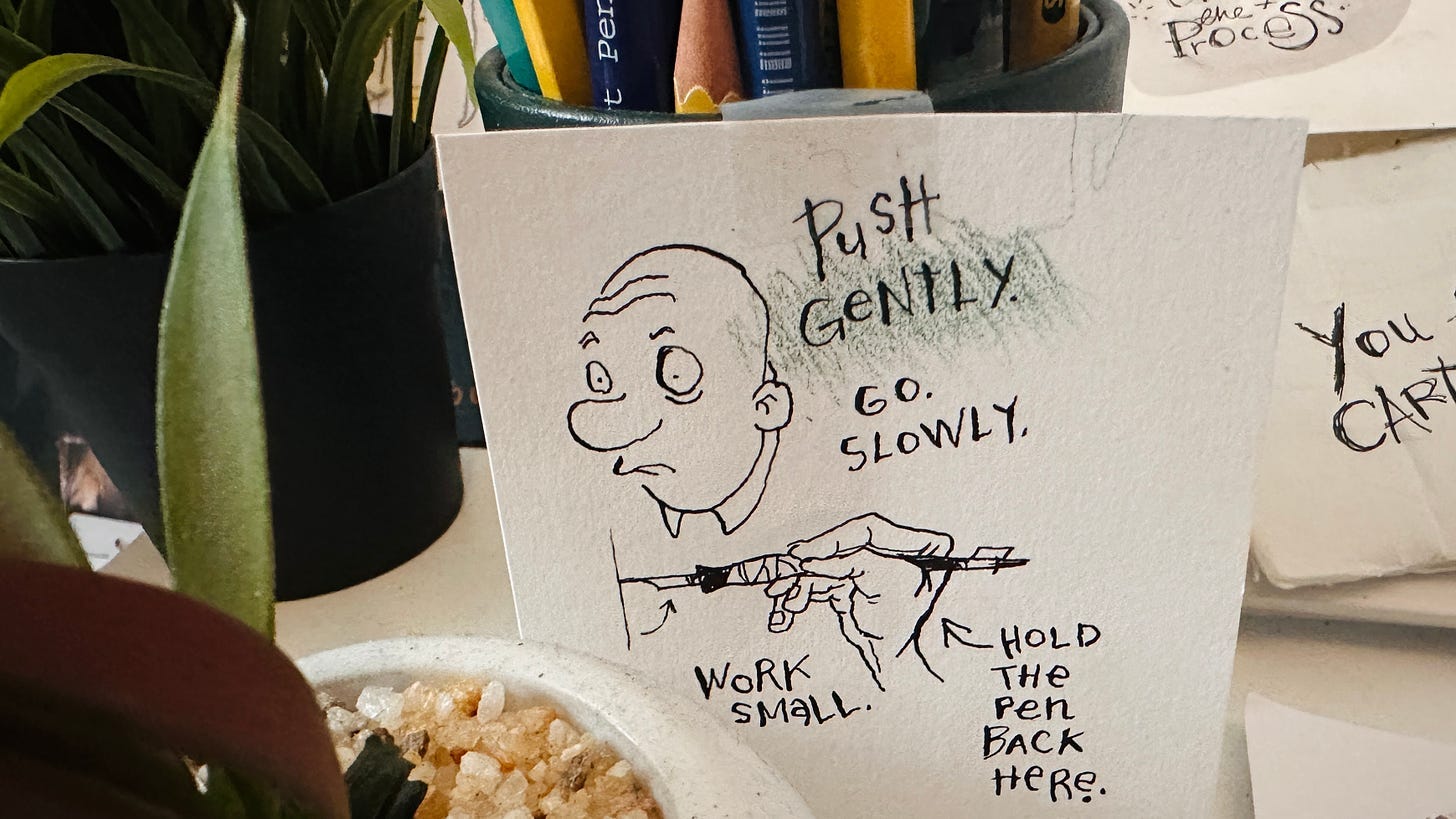

The free play in a sketchbook is essential for permitting yourself to make mistakes—as many as you possibly can—to discover and learn. Happy accidents yield enormous rewards if you allow yourself the confidence to make them. I still have to remind myself of this all the time, so I have it stuck above my drawing desk…

I engrossed myself with creative play for days, weeks, and months on end with this nib, trying every different method. I experimented with both the angle of the surface I was drawing on and the pen itself. I found a posture that felt like ‘me’ and began free-scribbling, filling sketchbooks, and burying my studio in a sea of paper scraps— not unlike Sorel’s controlled explosion. (Don’t worry, I recycled them all.)

I snipped off the end of the pen for just the right balance and wrapped the grip area in masking tape to give it slightly more heft in front. I kept a reminder of the posture on my drawing board. By all formal standards, my way of using this pen is completely “wrong” and deeply ill-advised, and I’m sure it’ll give me carpal tunnel syndrome by the time I’m 45. But you know how I feel about people telling me how to do things “the proper way”.

Anyway, it’s yours if you want to try it:

The work I’ve been able to produce since allowing myself the time and attention to figure out who I’m going to be when I wake up in the morning has been the most rewarding work of my career. I drew both of my last two books entirely using this nib. I’m about to start my third. For once, abject terror and anxiety are replaced with giddy excitement at the unpredictable chaos that awaits the page.

I’ve been able to publish work that looks and feels like the kind of mad hatter’s tea party my mind feels like for the first time in my entire career. And wouldn’t you know it, the following year, it resulted in my work getting nominated for not one, but two different award categories by the National Cartoonists Society. I feel like an idiot for holding my authentic voice in for so long.

Before I go, I should add that Sorel’s email did conclude on a nice, albeit bittersweet note:

“I suspect you always wanted to be a cartoonist. I can't give you any career advice until I hear you do stand-up. You might be brilliant at that, and should think about writing.

Now that print seems to be on the way out, I don't know how anyone can make a buck out of the internet, but maybe you can figure a way.”

Anyway. Here I am on Substack, figuring out a way.

Thanks for reading this far. I hope this helps you.

Share it with someone you think might enjoy reading it. That helps me a lot.

‘til next time,

You’re great at both

You should be a writer—and an illustrator/cartoonist.