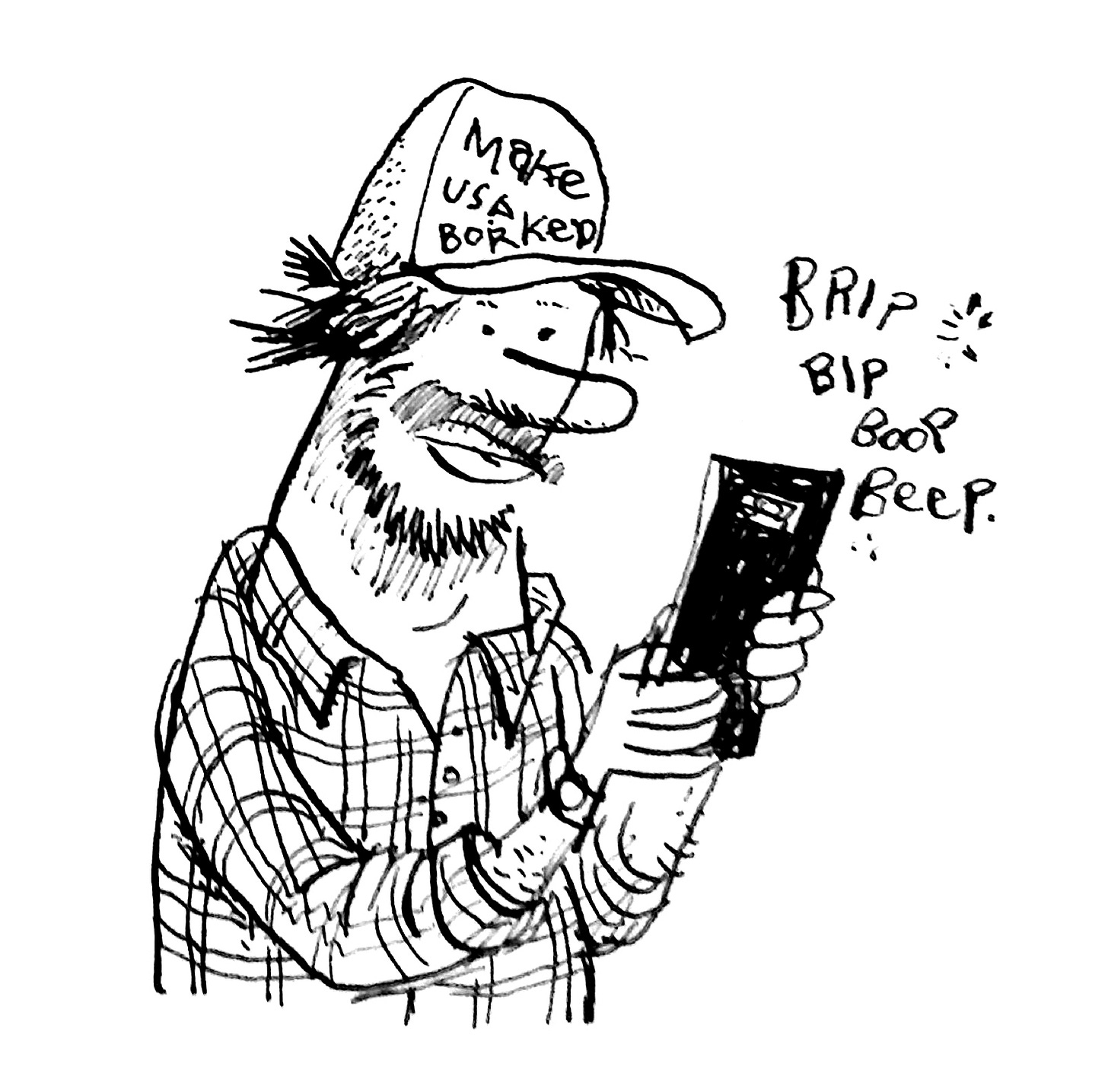

How to make a living drawing pictures in a world that keeps updating its software while you’re still installing the last update?

A pared down version of my guest lecture at FIT in New York

“Innovate inside the constraints. The constraints are changing faster than ever—budgets, tools, timelines, expectations—but the job hasn’t. The job is still to see clearly, make choices, and put a line down that could only have come from your hand.”

A few weeks back, an email landed: would I come to FIT and talk to illustration students about how to make a living drawing pictures in a world that keeps updating its software while you’re still installing the last update? I said yes before the imposter syndrome woke up and asked for coffee.

The brief was simple: come in, share the messy truth of freelance life, do a short drawing activity with the class. No slides required, but I brought some anyway, because nothing says “seasoned professional” like a Keynote that refuses to mirror to the projector.

If you enjoy my work and would like to support, please take out a premium subscription (just $1 per week)

How to Stay Human When the Tools Keep Changing

The very talented fellow New Yorker artist Jenny Kroik introduced me with a list of things I’ve done to pay the rent that was longer than my actual talk.

I didn’t go to college. I went to work. In 2004, I was a kid with no credentials and a second-hand Wacom Graphire tablet you had to look away from while you drew. (Imagine teaching your hand to write with a pencil while your eyes stare at the ceiling fan.) I embedded myself with people who were already doing the thing I wanted to do, kept my mouth open and my ears wider, and learned that survival in this field is mostly about two muscles: community and adaptability.

This is the essay version of that talk—tightened, cleaned up, and with fewer photos of my dog. The points haven’t changed: embed, adapt, double down on what’s uniquely yours, and build a direct line to your audience. The terrain, however, has.

1) Find the Table, Not Just the Tutorial

The best single piece of advice I’ve ever received: go sit with the people who are already where you want to be. Not to imitate them, but to absorb how they move—how they take feedback, price a job, survive a bad note, hit a deadline. Yes, retired veterans have wisdom. But the people actively doing it have something more perishable: live and current knowledge of what’s changing.

Early on I joined rooms. Real rooms. Rooms full of art directors, agency producers, illustrators, and other insomniacs. You learn faster in a room than in a comment thread. You also get hired more. Most of my best jobs came from other artists, not from agents. Agents are great when the big fish swims by, but it’s your peers who keep your calendar fed.

If you can’t find a room, make one: Society of Illustrators, National Cartoonists Society, MOCCA, SPX, CXC, Comic-Con. Go humbly. Ask specific questions. Offer specific help. Then follow up like a professional adult who owns a calendar.

2) Adaptability Beats Niche (Unless Your Niche Is You)

There’s an old religion in freelance illustration that says “niche down.” Be the Movie-Poster Person or the Cutaway-Diagram Person and corner that little cul-de-sac of the market. That used to be safer. Now the cul-de-sac has a sinkhole.

What wins, consistently, is being useful across formats while staying unmistakably yourself. Learn enough tools to pivot: Photoshop, Procreate, Clip Studio, Illustrator, traditional ink, and whatever new gizmo the client’s cousin swears is “industry standard.” Say yes, then figure it out. I’ve storyboarded ads on a Tuesday and hand-inked a poster on a Wednesday. Each job wants a different wrench.

But -and this is crucial- bring the same hand to all of it. Your line. Your choices. Your sensibility. Double down on the one thing no tool can do: you. It’s not a contradiction. It’s a glove: adaptability is the glove; your voice is the hand inside it.

3) The Phone Is Your Gallery Wall (Whether You Like It or Not)

Most people will meet your work on a phone screen. You can rail against this or design for it. I learned to think about scale, line weight, contrast, and legibility at 3 inches tall. That practice turned into real jobs—app portraits, email art, web illustrations—because the work read at the size where most eyeballs live.

This doesn’t mean “make everything simple.” It means make everything clear. Zoomed-in fussing is where hours go to die. Zoom out. Ask: does the gag land? Does the silhouette read? Does this color crash on a dim subway screen?

4) Build the Direct Line: Mailing List > Algorithm

I started New York Cartoons on Substack in 2020. I took it seriously in 2023. Consistency beat cleverness. Tuesday at 10 a.m. meant Tuesday at 10 a.m. Like a podcast, the cadence trained readers to show up. The quality can vary; the rhythm cannot.