If you ever need proof that art can outlast a civilisation, Peter Kuper might be the man to show you the receipts.

Our chat for Draw Me Anything #29 was one of those rare conversations where you come away feeling both creatively inspired and vaguely doomed. It was supposed to be about his new Fantagraphics book Wish We Weren’t Here, but it turned into a full-blown masterclass on evolution- of style, of species, and of humanity’s seemingly bottomless capacity for denial.

Peter has been rattling cages with ink since the late seventies, co-founding World War 3 Illustrated while still at Pratt in 1979. He’s drawn for The New Yorker, The Nation, Charlie Hebdo, and, of course, Mad Magazine, where he’s been steering Spy vs. Spy into its modern era. (“The stories of my death are highly overrated,” he joked, referring to MAD’s recent resurrection from the newsstand graveyard.)

He’s the kind of cartoonist whose output makes you feel like you’ve been napping through history. Political cartoons, graphic novels, weekly satire for Charlie Hebdo — and now, a wordless, apocalyptic art book that somehow makes the end of the world look …beautiful?

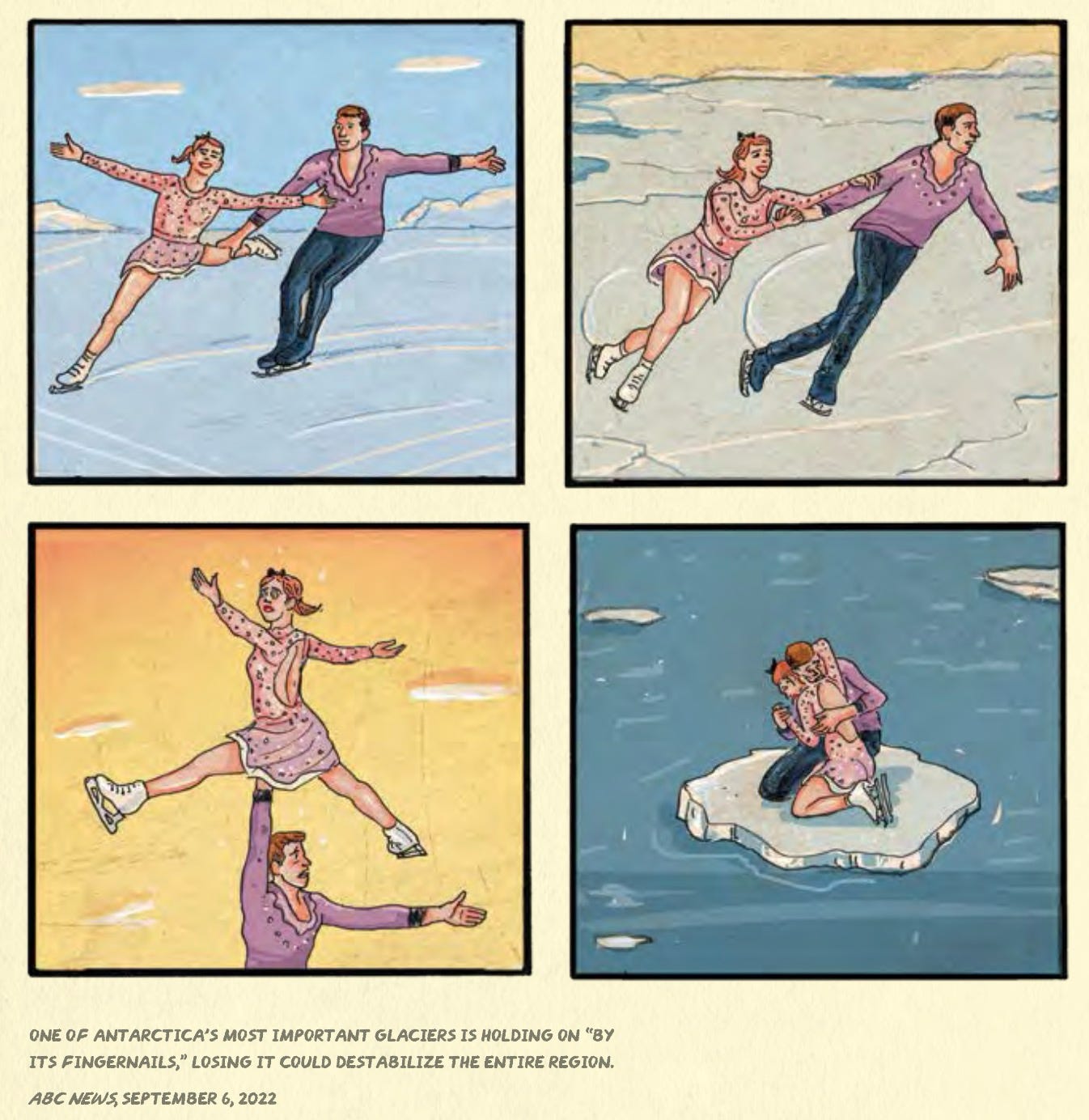

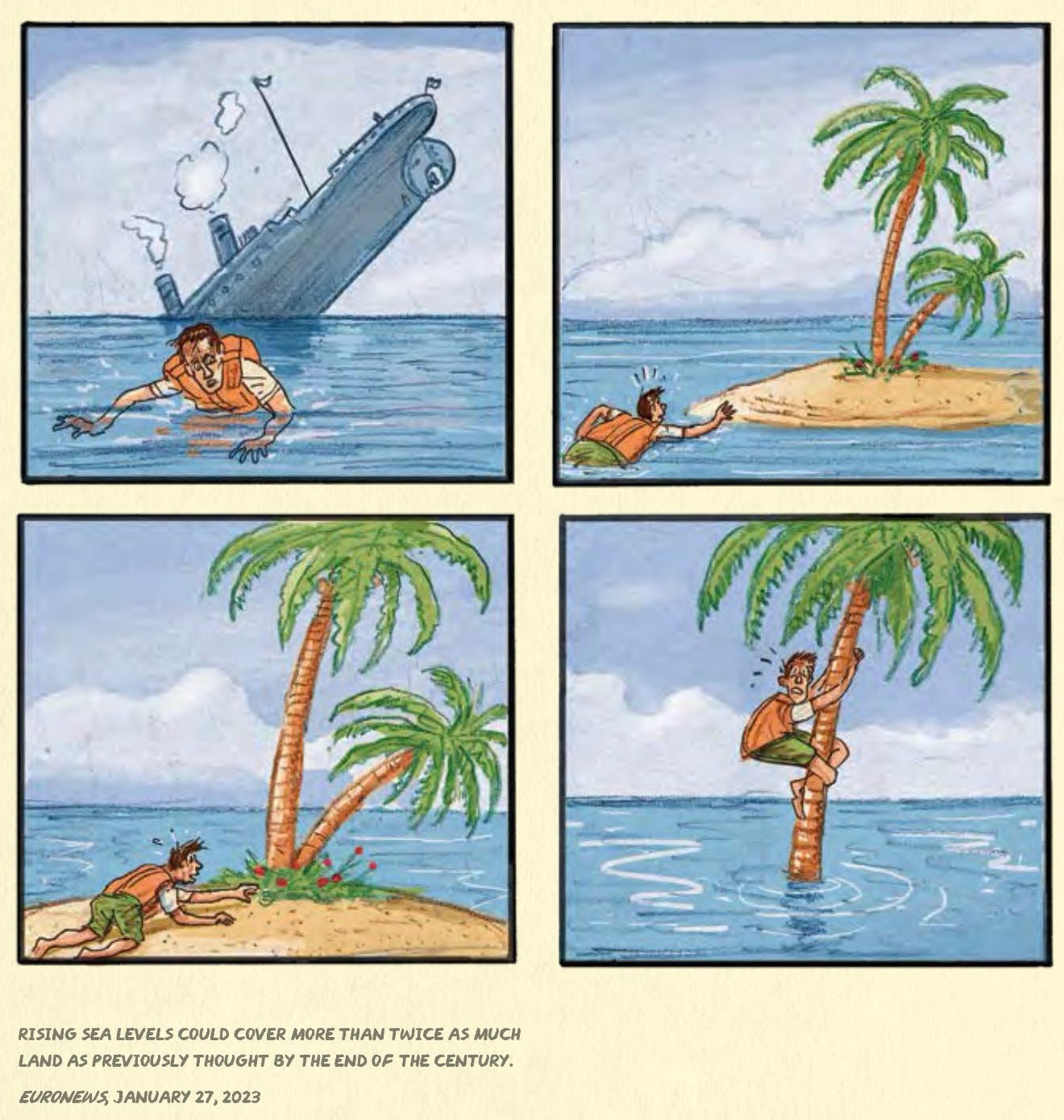

When I told him that Wish We Weren’t Here felt like a “global obituary in pictures,” he laughed, but didn’t disagree. Each four-panel page pairs a visual parable with a real news headline and date, grounding the surreal imagery in cold fact. It’s as if Kuper is saying: here’s the evidence, in case you were planning to deny the flood later.

He’s always been a translator between chaos and clarity. His drawings distil sprawling issues — climate collapse, disinformation, human greed — into images that bypass language entirely. “Wordless comics are like an international language,” he said. “You can show them to anyone.”

That instinct to strip things down goes back decades. Long before Spy vs. Spy, Kuper was carving linoleum prints and spray-painting stencils in a makeshift booth in his studio, inhaling more toxic fumes than a 1980s graffiti crew. “It’s ironic,” he said, “doing environmental cartoons while blowing toxic waste into the air.” Eventually, his lungs — and conscience — staged a revolt, pushing him toward cleaner methods like scratchboard and watercolour.

His approach to style is almost Darwinian: adapt or die. “Style’s like clothing,” he said. “If you wear it too long, it starts to smell.” Every few years, he sheds one aesthetic skin for another. Yet, even when his medium changes — from the razor-sharp linocuts of The System to the lush insect paintings of Insectopolis — it still unmistakably feels like a Kuper piece. The fingerprints remain, even if the materials don’t.

That restless evolution mirrors his subject matter. We talked about how Insectopolis grew from his lifelong fascination with bugs — a passion dating back to when a four-year-old Peter watched cicadas erupt from the New Jersey soil. (“I had a little sign on my desk that said ‘Peter Kuper, Entomologist.’”) That early obsession turned into decades of work connecting environmental systems, art, and the fragile lines between them.

During his COVID-era Cullman Fellowship at the New York Public Library, he found himself nearly alone in the marble halls during the pandemic, sketching butterflies migrating through empty corridors. “I started drawing monarchs in the architecture,” he said. “That’s when Insectopolis began.” In the book, insects aren’t just subjects — they’re metaphors for resilience, community, and collapse. “Without insects,” he reminded me, “humans wouldn’t survive.”

That idea extends into Wish We Weren’t Here, where the natural world and human greed clash in quiet horror. One of the book’s most striking images, an oil rig doubling as a syringe, injecting into a human arm, captures the self-destructive addiction of fossil-fuel culture better than a thousand think pieces.

His humour runs black and bone-dry. When I called him one of the most prolific cartoonists alive, he shrugged: “I stared into the abyss, and it told me to get to work.” Work, for him, is both a lifeline and a coping mechanism. “If I stop drawing,” he said, “I start thinking about what I’ve drawn, and that’s when I get horrified.”